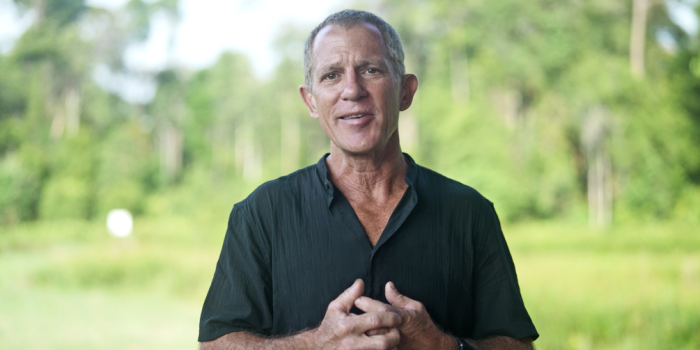

Some people find their calling in a boardroom. For Brad Sanders, it has always been the forest.

“I enjoy being in the forest with its green spaces and quiet places,” he says. “I think this goes back to my youngest days as a child with my grandmother in the foothills of Vermont.” That early connection to nature never left him, and after more than two decades in Indonesia, including the past nine years leading Restorasi Ekosistem Riau (RER), Brad’s commitment to conservation has only deepened.

RER is the flagship ecosystem restoration programme of APRIL, part of the RGE group of companies, focused on restoring peatland forests across the Kampar Peninsula and Padang Island on the east coast of Sumatra. Under Brad’s leadership, it has become one of the most ambitious private-sector conservation efforts in the Southeast Asia region, spanning biodiversity monitoring, forest restoration, and infrastructure development in some of the region’s most remote, waterlogged terrain. The conditions are tough – humid, isolated, and physically demanding – but the mission keeps him grounded.

“What drives me is that APRIL is doing the right thing,” he says. “I’m proud of RER, the direction of the company, and the targets and initiatives they want us to achieve.”

RER sits within APRIL’s broader APRIL2030 vision, under its Thriving Landscapes pillar, and is a long-term commitment to balancing commercial forestry with conservation, climate goals, and community development. With 150,000 hectares under protection and active restoration, the programme is both a personal passion for Brad and a global case study in landscape-scale conservation.

APRIL’s 1-for-1 commitment conserves and protects one hectare of natural forest for every hectare of plantation.

How RER is changing the role of business in conservation

RER’s model is based on collaboration between communities, NGOs, local authorities and APRIL. It is a strategic bet by APRIL on the long-term value of ecological stewardship.

“We take active responsibility to manage the land ourselves,” Brad explains. “We are active managers, with field teams that provide a direct line of visibility to the ground.”

Rather than funding external groups, APRIL directly oversees the protection of 150,000 hectares of forest, working out to roughly a third of its 1-for-1 commitment, which ties every hectare of production forest to an equivalent hectare of conservation land. This isn’t just symbolic.

This approach came about following the introduction in 2007 of Indonesia’s Ecosystem Restoration Concession (ERC) licence, which allows private companies to hold forest licences for conservation and restoration, rather than timber extraction. “Just having the regulation in place to allow for this is a real bonus for Indonesia and for private companies that are motivated to do conservation work,” Brad says.

It also means APRIL can take a long-term view, something many donor-dependent conservation efforts can’t afford. “We’re not looking for external funding,” Brad notes. “We’re generating the funds to pay for conservation internally.”

The result is a model of hands-on, corporate-driven restoration that spans fire prevention, forest and hydrology restoration, biodiversity monitoring, and community engagement, all carried out by in-house teams.

Camera traps collect data on wildlife and vegetation change, creating one of the region’s most comprehensive ecological data sets.

Managing tough conservation challenges

RER’s work takes place in some of Indonesia’s most challenging terrain: vast, waterlogged landscapes where traditional infrastructure is limited, and access often requires boats or trekking through flooded trails. “Peatlands are very difficult places to navigate,” Brad says. “They’re wet, isolated, with very little access. Trails are often flooded.”

Despite the harsh conditions, Brad and his team have made measurable progress. Field staff operate in physically demanding environments, often working waist-deep in water to monitor, restore, and protect the land. Their dedication is foundational to the programme’s success. “You really have to appreciate the hard work and dedication of the teams in the field,” he says. “They’re out there, in the thick of it, for long periods of time.”

But it’s not just the landscape that’s challenging. RER must also navigate threats common to many conservation areas, including illegal logging, forest encroachment, and fire risk. This is where the programme’s unique landscape approach makes a difference. APRIL’s surrounding plantation areas act as protective buffers, reducing external pressure on RER’s conservation zones. In places where this buffer isn’t present, the team employs additional strategies to monitor and secure vulnerable areas.

These efforts are paying off. On the Kampar Peninsula, RER has recorded more than a decade without major fire or illegal logging incidents. This is a sign not only of the effectiveness of its protection strategy, but of a recovering ecosystem. “The forest is resting,” Brad says. “It’s recovering. This is the longest rest period this patch of forest has had in the past three decades.”

Protect, restore, prove: the science of long-term impact

RER’s approach is about proving restoration works, backed by data.

“We’re collecting data on everything,” Brad says. “Wildlife, vegetation, water levels… and we’ve been doing it consistently for over a decade.”

Using camera traps, biodiversity transects, and hydrology monitoring, RER has built one of the region’s most comprehensive ecological data sets. This data is now supporting research by international universities like the University of Kent, University of South Wales and University of Göttingen, spanning topics from wildlife behaviour to paleoecology.

“It’s taken time to start seeing trends,” Brad notes, “but now we can really show people what’s happening in the landscape.”

The evidence is encouraging. Peatland water tables are stabilising, wildlife occupancy is increasing, and the forest is recovering, offering growing potential for climate resilience and carbon storage.

Most of all, the science reinforces a larger point: long-term, privately funded conservation can deliver measurable environmental outcomes when it’s consistent, collaborative, and backed by real commitment.

A decade of observation has shown peatland water tables stabilising, wildlife occupancy increasing, and the forest recovering.

Technology as a conservation force multiplier

In RER’s remote, waterlogged landscapes, technology is essential to getting things done efficiently and accurately.

“We’re making use of GPS, drones, and tools like the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) to help us with data collection and documentation,” Brad explains.

These tools support everything from fire detection to mapping vegetation and tracking wildlife. With SMART, field teams record data via tablets in real time, helping managers monitor activity and respond quickly when issues arise.

But technology is only as useful as the insights it enables. “Just collecting data is not enough,” Brad adds. “Analysing it is very important, and we’re working with universities and academics to do statistically valid analysis.”

Balancing business and ecology: the private sector’s role

Brad believes that conservation is a crucial part of how sustainable businesses should work.

“We are land dependent and rely on natural resources to produce our products,” he says. “Being environmentally and financially sustainable are both critical to long-term business success. If you’re overexploiting and only focusing on profit, you’re not going to be in business for very long.”

RER’s integrated approach reflects this thinking. It’s not outsourced or symbolic. It’s embedded within APRIL’s business strategy. It’s resourced, staffed, and managed internally. Brad’s team doesn’t just advise from the sidelines. They’re on the ground every day, restoring degraded land, blocking canals to rewet peat, and preventing fires before they start.

The surrounding plantation areas also serve multiple purposes, supporting production, functioning as a buffer zones that protect RER’s core conservation forest from fire and encroachment, and as extended habitat for a variety of wildlife species. Where gaps exist in this protective ring, additional patrols and safeguards are deployed to keep the landscape intact.

While many companies treat sustainability as a checkbox, Brad sees it as a commitment that must be earned over time. “We’re trying to show a positive example of how you can manage a large area of land not just for production, but for protection as well,” he says.

RER plays a crucial role in conserving the habitat of the critically endangered Sunda pangolin.

What the next generation needs to know

Conservation work isn’t for everyone. “It’s tough. You’re out in the heat, far from home, friends, and the usual comforts,” Brad admits. When he meets someone genuinely passionate about the work, he makes it a point to support them. “What I look for is motivation and initiative. In the field, you’re going to face hardship. You have to be able to enjoy the work.”

To those sceptical of private-sector conservation, Brad has a simple message: come see it for yourself. “The scepticism is well deserved, given the region’s history,” he says. “But we’re doing things differently. If you’ve got ideas, visit us, work with us, let’s make them happen.”

Learn more about the people of RER and the vital work they do: https://www.rekoforest.org/media-centre/news/